When you begin growing vegetables and raising animals on even the very smallest of farms, you quickly learn that there are three uber-important issues to deal with: 1) Land, of course. (How much space do you have? How healthy is your soil?) 2) Water. (Where is your source? How will you get it to where you need it? Will you have enough?) and 3. Structures. (Where will you need them? How will you build them?)

When you begin growing vegetables and raising animals on even the very smallest of farms, you quickly learn that there are three uber-important issues to deal with: 1) Land, of course. (How much space do you have? How healthy is your soil?) 2) Water. (Where is your source? How will you get it to where you need it? Will you have enough?) and 3. Structures. (Where will you need them? How will you build them?)

Number three might surprise you. But as I walked around the farm in the snow this morning, indulging myself in photos of frosted branches and frolicking hens, I realized how often I focused on the door of a shed, the mullions of a window, the turn of a gate. Out in the back field, I stopped to turn around and take a picture of the farm from afar, and I realized just how many structures Roy has built since we moved here.

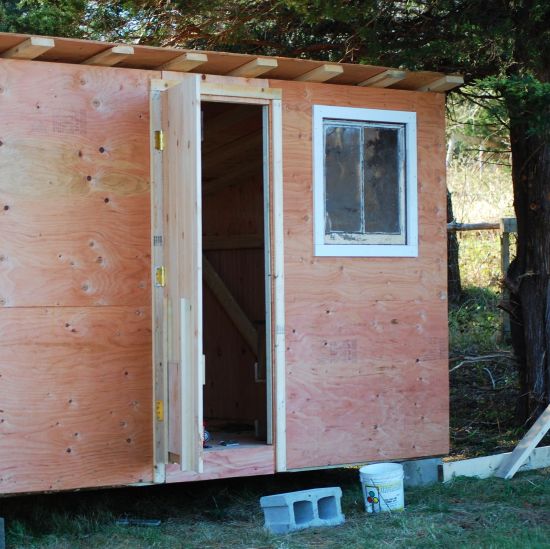

While the chickens are happy to hop about the snow (which they sort of peck at instead of drinking their partially frozen water), they dart in and out of their coops when the wind comes up. (Outside, they keep themselves warm by puffing up their feathers to trap air.) And tonight when the bitter cold and wind comes, they will be warm, bunched up together on their roosts, inside their locked coops, safe from predators. We have 8 coops now—one in the process of being converted into a duck house. One coop also incorporates a small area for holding grain.

We have a farm stand structure, which includes a back room where we do all our egg processing. (The front functions as the farm stand and holds the egg refrigerator for customers.)

We have a farm stand structure, which includes a back room where we do all our egg processing. (The front functions as the farm stand and holds the egg refrigerator for customers.)

We have two tool sheds and one grain bin/shed. Roy has converted part of one of the tool sheds into a “walk-in,” an insulated room for keeping eggs from freezing.

The grain bin down by our five biggest coops holds some hay for nesting boxes and coop floors, too. But we could use a bigger area to store hay.

And of course we have the hoop house, where much to my dismay, everything—kale, collards, baby bok choy, lettuce, arugula—is thriving, despite this cold.

Everything inside the hoop house is also under two layers of cover—one fabric, one plastic. And the actual temperature in there this morning was above freezing!

The hoop house is an incredible structure—not only does it protect from the elements, but based on what we’ve sold out of it versus how much it cost to build, it’s a money-maker, too.

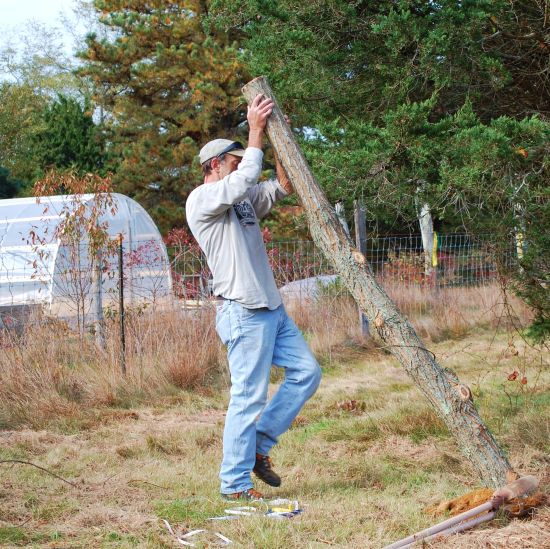

And fencing—well, that is one of your top-of-the-list structures on a farm. Lots of post-hole digging and deer-fence-erecting went on here, not only to protect our crops, but to create very large (semi-)protected pastures for our chickens. (Additional guy wires cover the pens; they’re intended to discourage hawks but don’t always work.) We were lucky to have a good deal of property-delineating fencing (like that above) in place when we arrived.

We don’t have a barn—yet. Roy has converted a small former garage on the property into his workshop. Long ago, there was a grand barn on this farm (the remaining stone foundation is where we housed the pigs this summer), but it would cost a fortune to erect a new one there. (Oh, and the pig pen itself was another structure! The stone foundation formed three walls, but Roy repurposed old railroad ties and wood pallets to make a secure fourth wall and gate.)

Which brings me around to the cost-of-structure issue. Always a good idea to look far ahead and budget for these things, as we did this year for the farm stand, the new coops, and the grain bin.

Which brings me around to the cost-of-structure issue. Always a good idea to look far ahead and budget for these things, as we did this year for the farm stand, the new coops, and the grain bin.

And then, salvage, salvage, salvage.

Roy recycles as much old (usable) wood, windows, doors and hardware as he can. (People actually bring us stuff now, too—recycling is a way of life here on the Island. Witness the compost pile, below, of donated horse manure.)

But of course you need someone to do the building, too. We are very lucky here on Green Island Farm to have a farmer who is also a licensed builder, but partnering or bartering with someone with carpentry skills can be a good plan. Keeping the structures as simple and efficient as possible is important, too. For a small operation on a budget, fancy is not practical. Also, living with a problem for a little while, if possible, can present the best solution.

All this reminds me to tell you that I’m pretty excited that some of our resident builder’s designs have been included in a special appendix in my new book. So when you get your copy of Fresh From the Farm, be sure to turn to the back of the book for drawings of a great small chicken coop, a basic farm stand, a covered raised bed, and a seed-starting system. (Thank you, Roy!)

All this reminds me to tell you that I’m pretty excited that some of our resident builder’s designs have been included in a special appendix in my new book. So when you get your copy of Fresh From the Farm, be sure to turn to the back of the book for drawings of a great small chicken coop, a basic farm stand, a covered raised bed, and a seed-starting system. (Thank you, Roy!)

In the meantime, stay warm and dry. (I almost forgot that part—you need a house, too, to shelter the farmers. Nothing fancy, though. Remember, they don’t spend too much time inside.)